"Shauka - Borderland Tribe" is the first part of The Lost Culture Behind Dialects, a series of projects exploring different dialects and their cultural significance. Centered around the Shauka community, a borderland tribe whose dialect and traditions are slowly fading, the project examines how linguistic shifts impact heritage and identity. As dominant languages exert influence, these dialects are gradually disappearing, leaving younger generations distanced from their roots and often unaware of the depth of knowledge embedded in their native tongue.

Here, the artist explores how dialects serve as a bridge between past and present—whether in traditional medicine, where healing practices have been passed down for centuries, or in food and architecture, where ancestral wisdom continues to shape daily life. But as external linguistic influences grow and widely spoken languages take precedence, the intimate connection between words and cultural identity weakens, threatening to erase a vast repository of indigenous knowledge.

curated by

Vijay singh Bisht

Earlier, some English writers attempted to write about the Shaukas. They did not conduct an in-depth study. If they studied anything, it was merely the facial features of the Shaukas. After that, Indian writers also relied on these same books. Shauka (Rung) is a caste, but they were called Bhotia, whereas the well-acquainted and closely connected Kumaonis and Nepalis always referred to them as Shauka.

They are neither Bhotia nor is their region Bhot. The Shauka tribe resides not only in this region but also in Johar, the Niti-Mana valleys of Chamoli district, and the Dullu, Bajhang, Sitola, Rapla, and Byans panchayats of Nepal. This article focuses solely on the Darma pargana. Hence, in this book, the Shauka region refers to the Byans, Chaudans, and Darma pattis.

Shauka Region Geographical Introduction

This well-known Shauka region of Uttarakhand is located on the borders of two countries. The route to the sacred pilgrimage site of Manasarovar in Manas Khand is described in such a way that it gives us an idea of the location of the Shauka region.

On this sacred pilgrimage route lies the northern-eastern Shauka region of the Pithoragarh district, which is known as Darchula Tehsil. Darchula, located to the northeast of Pithoragarh town, is the gateway to the Shauka region. If we include the winter residential areas of the Shaukas, then Jauljibi, situated at the confluence of Kali and Gauri, can be considered the gateway.

The upper and western valley of the Kali River (Mahakali), along with the Kuti River valley, which merges in Gunji, encompasses the Byans Patti. Flowing southward, the Kali River separates the Chaudansh Patti from Nepal. At Tawaghat, the Dhauli River, coming from the northwest, merges into the Kali River. The valley of this very Dhauli contains the Malla and Talla Darma Pattis. This region, divided into these four pattis, is collectively called Pargana Darma.

Pargana Darma's Shauka Region The Shauka region of Pargana Darma is separated by international borders with China (Tibet) to the north and east, and Nepal. To the north lies China (Tibet), while to the east is Nepal's Mahakali Anchal, specifically Darchula district. To avoid misleading the reader, it is necessary to clarify that the Indian part of the Shauka region, Darchula, is a tehsil, whereas the adjacent Nepalese region, also called Darchula (spelled Darchula in Nepal), is a district.

To the south lies the Malla Askot Patti of Didihat Tehsil, which was formerly under the authority of the Raja of Askot. To the west lies the Johar region (also part of the Shauka region) of Munsiyari Tehsil and the non-Shauka area of Darchula Tehsil.

The Shauka region spans elevations from 2500 feet to 22,661 feet above sea level. On the map of India, a glance at the mountainous terrain reveals that this area falls under the Middle Himalayas or Kumaon Himalayas. According to Pandit Rahul Sankrityayan, the area north of the line connecting Askot and Kapkot constitutes "Bhot" (the Shauka region). If we include the eastern part adjoining Nepal, the Shauka region of Pargana Darma becomes clearly defined.

If we exclude the winter residential areas, the entire Shauka region lies above an elevation of 7,000 feet. The inhabited areas of the Shaukas are found between 7,000 and 12,000 feet.

From Patti Byans, there is a pass leading to Tibet at an elevation of 16,800 feet. In Patti Byans, near Kuti village, are the Mad Syang or Limpiyadhura Pass (18,050 feet) and the Leleong Pass (17,400 feet). In Darma, the Syala Pass (16,650 feet) and Darma Darsh Pass (18,510 feet) are located. At the eastern edge of this region, in Tinkar (Nepal), lies the Tinkar Pass at 16,800 feet. These passes were only accessible during the summer months for 5–6 months of the year. These high peaks are situated approximately 40–45 km south of the Himalayan range bordering Tibet. The highest peak, Panchachuli, is in Darma, towering at 22,661 feet, surrounded by four other peaks.

This Shauka region can be divided into two parts: the Kali Valley and the Dhauli Valley. In the eastern region, the Kali River originates from Kalapani (12,000 feet). Flowing through Kanwa Manila, it merges with the Kuti River and forms a wide U-shaped valley until Gabryang. From Gabryang (10,330 feet) to Boondi village (8,800 feet), the Kali River descends 1,200 feet over a horizontal distance of one mile. It then flows through gorge-like narrow valleys, defining the boundary between Patti Chaudansh and Nepal. Apart from the terraced narrow plains of Gabryang, Naplachyo, Gunji, Nabi, and Raokang, the entire Chaudansh and Boondi village area is extremely rugged.

Tawaghat is the confluence of the Dhauli and Kali Rivers. This spot should be considered the gateway to the permanent residential areas of the Shaukas. It is also the last point reachable by motor vehicles en route to this sacred place. Beyond this point, the towering peaks and the enchanting natural scenery captivate the eyes. When the mountain-dwelling Shaukas leave their temporary winter residences for their permanent (summer) residences, the land of Tawaghat welcomes them. Their hearts long to reach the sacred soil near Dharmashram (Darma), Chaturdrisht (Chaudansh), Byasashram (Byans), the hermitage of Byas Muni, and the divine land of Kailash Dham.

The Shauka people reside in the following villages. Originally, these were permanent settlements; however, for several thousand years, residents of Patti Byans and Malla Darma have experienced residential shifts. The villages and their respective sub-castes are as follows:

Villages of Shauka with winter residence cast and sub caste

Choudash Kali Valley

Dhuali Valley Darma upper and lower part

Two Nepali Shauka Villages of in Byans valley

Geographical structure

To understand the geographical structure of this region, a brief knowledge of the origin of the Himalayas seems necessary. When all the continents of the Earth's crust were once joined together, it was called Pangaea. In the middle of this, there was a narrow sea running from east to west, which the geologist calls the Tethys Sea. Over a long period, sediment such as soil, gravel, and stones accumulated on both sides of this sea. Possibly, living organisms also accumulated. Over time, due to an unknown force, the landmasses on both sides of the Tethys Sea (Gondwana and Angara land) moved towards each other, causing the sediments that had accumulated in the Tethys Sea to rise. This uplifted area is the Himalayan Mountain range. The water of the Tethys Sea sank into the earth beneath the base of the Himalayas. The region from Gabryang to the top of Lipulekh is named the Tethys Himalayas due to the accumulation of sediments. These sediments accumulated at different times, leading to the formation of layers. The rocks of the Himalayas are layered. If we divide the Himalayas from east to west, the Shauka region falls under the 'Kumaon Himalayas'. This region lies at the northeastern edge of the Kumaon Himalayas and is connected with the Tibetan and Nepalese Himalayas.

Water Flow Systems

Kuti River

Dhauli River

Seasons in Shouka Region

The climate of the Shauka region is completely influenced by its geographical layout, with the height and extent of mountain ranges playing a key role. Based on the maps of H. G. Center and L. D. Stamp, this region can be classified under the 'Himalayan Climate' zone. According to altitude, the climate here is polar.

Yanai- This is the hottest season of the year. Temperatures begin to rise in March, reaching their peak in April. By June, the temperature starts to fall. During this season, the air remains dry.

Shyel- The amount of water vapor that hangs over the vegetation is called Shyel. The season is named after the high presence of Shyel, which occurs during this time. With the arrival of the monsoon winds, temperatures begin to drop. The monsoon rains start in mid-July, and sometimes heavy rainfall continues for weeks. During this season, the rainfall reaches 40 to 60 mm.

Ghunchai- Ghunchai is the winter season. The terrain above 6000 feet remains snow-covered during this time. Above 8000 feet, snow does not easily melt. Precipitation occurs in the form of snow. The days are sunny, but the nights, mornings, and evenings are extremely cold. It is believed that winds entering India from Afghanistan assist in the snowfall here. These winds begin to affect the region from December. In areas above 8000 feet, crops remain buried under snow. Animals and birds living at higher altitudes descend to lower valleys. The Shauka people move to lower valleys in Dharchula and Nepal. In early March, as the temperature rises, the snow starts to melt, and the crops, soil, and vegetation covered by snow in November, December, January, and February become visible again.

Vegetation

The vegetation of the Shauka region is classified as "Himalayan".

Main Trees of the Shauka Region

1. Himalayan Cypress (Cypresses Torulosis)

This tree grows up to a maximum height of 150 feet and has a diameter ranging from 12 to 16 feet. It is a valuable timber tree and is found predominantly at altitudes of around 10,000 feet.

2. Pinus Longifolia

Found at altitudes between 9,000 and 11,000 feet, this tree provides high-quality timber that is better than Kail. Its fruits are used to make ink.

3. Birch

Found between 11,000 and 13,000 feet, this tree marks the upper limit of tree growth. The bark of this tree is used to make "Syola" (Bhojpatra). Other valuable timber trees include Tangsthin and Kansthin.

4. Wild Rose

This thorny tree produces fruits and its roots are used to prepare tea.

5. Juniper

A variant of Deodar, Pama trees are found above 10,000 feet. Its needle-like leaves are used to make incense. The green branches and leaves are used as fuel in villages like Kuti and Tinkar.

The forests of this region yield a variety of valuable items. High-altitude areas are rich in medicinal herbs and precious grasses. Some valuable fruits are also found here. The seeds of these plants were once stored and exported abroad from the Shri Narayan Ashram in Patti Chaudas. Ringal (Khi) is used to make mats and baskets. The bark of the Kilmuru tree and the root of the Chirchya plant are used to prepare dyes. Various types of wild vegetables are found in abundance in this area. Some important plants are Rasyin, Gangari, Chhamasyin, Kipansthin, Nhari, Pangar, Kanasyin, Belakasyn, Dhyar (Deodar), Patakchay, Sirasyin, etc. Fruit-bearing trees include Feralyu, Chook Dandali, Guldum, Retapli, Mangali, Mutali, and more.

Wild vegetables found above 9,000 feet include Yakan, Tampilyu, Khakan, Machakan, and Damkan. Below 9,000 feet, vegetables like Hetu, Lungriya, Mokasya, Pyetapyeta, and Pachoo (Bichhoo) are found. Spices found in the wild include Mayin, Pandan, Lidam, and Dhai. Medicinal herbs include Gyen (Banka), Rilbu (Brikhalu), etc. Pangar fruits, Khakan, Panchyuli, and Khush are abundant in this region and are used for washing clothes

Shauka Ethnic Introduction

In the Hindu varna system, there are four varnas: Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra. The Shauka community identifies itself as belonging to the Kshatriya varna. To validate this claim, it seems necessary to examine the meanings of words that define their identity as a community. In their own language, the Shauka refer to themselves as belonging to the "Rang" community. The word "Rang" has another literal meaning: "arm."

In present times, the caste system is no longer determined by deeds but by heredity. However, in the Shauka community, caste distinctions are still determined by actions. For instance, in the Gwan (funeral rites) ritual, only an Amricha performs the duties of a Brahmin. A Dangariya (a person into whom deities manifest) is revered in the community due to their exemplary and noble deeds and is accorded the status of a Brahmin.

In some cases, the lineage or clan of a Dangariya (Lama) is identified with a specific gotra or rath, and they are given the title of "Lamam" gotra or rath to define their caste.

In this region, sub-castes have been formed based on village names. For example, people from Garbyag are known as Garbyal, from Nabi as Nabiyaal, from Sirka as Sirkhal, and from Gwu as Gwal. This is similar to how people from Ludhiana are called Ludhianvi, from Moradabad as Moradabadi, or from Almora as Almordiya. The mere fact that people belong to different villages signifies this distinction. In local folklore, tales of death rituals, and folk songs, references to these sub-castes can also be found, although these terms are no longer in common usage. They have been described earlier. These caste-related words mentioned in folk songs and stories are derived from the residents' places of habitation, the characteristics of those places, etc. A couple of examples will make this clearer. The Budiyals of Bundi once lived near Okhad Bundi. The village was divided into two parts: Kondyer and Yawn. The residents of Kondyer were called Kondmpa (Kondnchan). Later, when they moved to the present village, they came to be known as Budiyal. Though the village of Pankayer was buried due to the collapse of the Pankayer mountain, the name Kondyer still persists. The villagers of Bundi, who worship their ancestors, still annually worship Yimi (an ancient person) at the location called Kondyer. The Garbyals are also referred to as Jhuharu. The ancient village of Garthyog was divided into two neighborhoods. The Nabiyaals from Nabi village are called Shyibypa. In fact, Nabi village (Shyed - white, Byi - rock, mountain) is situated on a white naked mountain. Even the current village's name, Dabi (Nabi), is derived from this mountain or rock.

Shauka - Social and Cultural Introduction

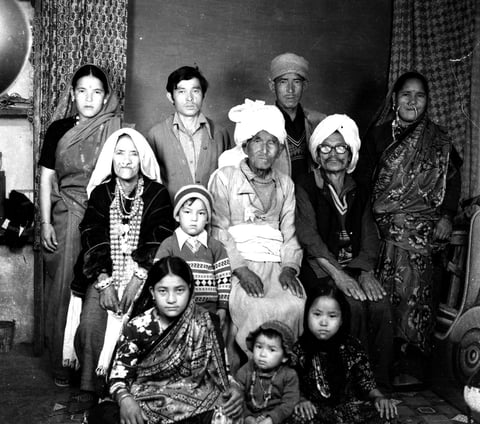

Family and Society

In the Shauka dialect, the word for family is "द," which also means "smoke" in another context. Since the number of members in a family can vary, but there is only one hearth, the word "Khu" is an appropriate term for family. Another word used for this is "Mau." Like in other regions, this society also follows a patriarchal family structure. The father or the elder male member of the family is the head and the decision-maker. The family lineage is carried forward through the father’s name. In case of adoption, the family lineage follows the gotra of the adopted son. If a person has no offspring and is concerned about the lineage not continuing, the second son of a brother or any other person can be adopted as a dharmaputra (spiritual son). It is essential for every member to follow the orders of the head of the family. Tasks in daily life are naturally divided among the members. The women take care of the hearth and household chores, while the men are responsible for gathering food and trade. This labor division may change depending on the circumstances.

In Patti Byans, the male members of the community used to go to Tibet for trade. As a result, along with cooking, agricultural work also remained under the responsibility of the women. In Patti Chaudansh, agriculture has been the primary profession. Therefore, women are mostly engaged in agricultural work, while the men assist in food preparation.

In this society, the joint family system sometimes lasts for a long time, and at other times, as soon as all the brothers are able to stand on their own feet, the family is divided to avoid conflicts. The father’s property is divided among his sons. Due to the daughter-in-law’s opposing views toward the mother-in-law, there have sometimes been divisions between father and son. However, the son continues to fulfill his duties and responsibilities toward his parents as before. The reason for the division between brothers is not due to conflict between them but rather due to the responsibilities of the daughters-in-law, such as handling business, earning money, and managing food, clothing, and shelter.

Women are entrusted with preparing food, raising children, plowing the fields, as well as all agricultural tasks and wool work. The head of the family is respected, and therefore, the first plate of food served is given to the head of the family. Any family activity requires their prior approval. In the living room, the head of the family sits at the farthest end (Thokolchyo). Among the women, the eldest member of the family (the daughter-in-law or housewife) holds a high position. She is referred to as "Mulin Rani" or "Queen of the Hearth." Other women can prepare food, but the task of serving the meal is solely her responsibility. If the housewife (Mulin Rani) or mother-in-law becomes incapable with age, the responsibility falls to the daughter-in-law. The care of household utensils, agricultural tools, the supervision of animals (at home), and overseeing food supplies are also her duties. The young men gather firewood, plow the fields, and assist their father or elder brothers in business. The girls help with fetching water, washing dishes, serving food, grinding grain in the mortar, cutting grass, and other agricultural tasks.

Marriage Ceremony

In the Shauka community, the wedding celebration is the most joyous and exuberant of all rituals. For a few days, not only the bride and groom but also their families, the entire village, and relatives experience a time of happiness. The entire village and community rejoice, expressing their joy, singing, dancing, drinking, and engaging in entertainment, all while wishing for a prosperous, harmonious married life and a bright future for the couple. Every villager and relative shares in the happiness of the bride and groom equally. Like other Hindus, the Shaukas follow a monogamous system, where one man and one woman live as husband and wife.

Before year 2000, the practice of abduction marriage was prevalent here. This was alongside the Thochimo v Dekhant tradition that had been followed for some time. According to this practice, the boy, or he along with his friends, would abduct the girl without the knowledge of her parents. The assistance of others from the girl’s village was involved, who were informed in advance and knew the timing of the abduction. This practice is similar to the Aparatiya tradition of the Ho people. Such an act was only possible when the girl's parents disapproved of the match or could not afford the expenses of a traditional wedding. Since the abduction was carried out without the knowledge or consent of the parents, night time was considered appropriate, though it could also occur during the day depending on the situation. Even if the parents agreed, the reason for the abduction was that poor parents could not afford the costly customs of marriage. Therefore, indirectly, they would signal that they were open to the abduction. In cases where the parents explicitly rejected the marriage, there would often be violence between the groom and bride’s families. In some cases, violent incidents would occur. During such abductions, the bride’s family would often ask the girl, "Man se la zor se?" meaning “Is it of your own will or have you been forcefully brought here?” However, according to societal etiquette, even if the girl agrees willingly, she is expected to reply that she came “against her will.”

Another prevalent marriage tradition here is Gandharva marriage or Marriage by mutual consent, which could also be considered Love marriage. This type of marriage is occasionally heard of in the community. When a couple decides to live a married life and their guardians or parents do not approve, the couple elopes. Until the boy’s parents invite them back, they live away from the parents and society, becoming self-reliant and leading a married life.

Another characteristic of abduction marriage is as follows: When the groom abducts the bride and she enters the groom's house (threshold), eats a piece of sattu (roasted barley flour cake) and drinks a cup of liquor, the principal ritual of the marriage is considered complete. If the bride’s parents later deem the groom unworthy or decide to stop the marriage for any other reason, the bride is considered the groom’s property. The man who abducted her then gains full rights and can claim her as his wife in front of the Panchmandal (council of five elders).

In the Shauka community, although divorce is permitted, instances of divorce are rare. In cases of abduction marriage, abduction is only possible if the bride consents through taram (a sign or approval), and it is known that her parents will not approve. The bride's parents and the male villagers assess the groom and bride to decide the engagement. If a husband and wife are dissatisfied with each other, divorce may become a matter for discussion. The term for divorce is 'dharma' or kolti.

This dissatisfaction may stem from one party's misbehavior. Divorce is usually initiated by the wife, and a dharma meeting (a council) is called for. The husband does not directly request the divorce. If the husband desires separation, he would act in a way that compels the wife to seek divorce. Divorce means 'giving dharma,' not 'taking it.' The wife may return to her parental home, but the husband cannot marry another woman unless clear proof of misbehavior is presented.

The term dharma here signifies purity in conduct, actions, and behavior. Both husband and wife must maintain good conduct and fulfill their duties to each other. If there is a failure in this conduct, then the concept of dharma no longer exists, and the only option left is to separate their lives, allowing each to follow their own path of dharma.

Dialect Language

Many writers have used their pens to describe the Shaukas, classifying their language within the Tibetan-Burman or Chinese linguistic families. But the original form of the Shauka dialect dates back to the pre-Vedic Dravidian (Munda) language, which later blended with the Vedic Aryan language. Over time, it continued to incorporate elements from various other languages.

The original form of the Shauka dialect belongs to the Austric family, predating the Dravidian languages. The earliest inhabitants of the Indian subcontinent spoke this dialect. Max Müller referred to these people as 'Munda.' Among the Munda people, the counting system was based on increments of twenty, rather than the base-ten system typical of European cultures. This practice is evident among the Shaukas as well. For instance, the term nassa represents 20, and the Pithoragarh dialect exhibits some influence of the base-ten system. However, the imposed system of counting in forties (nassa sumsa = 30) never gained full acceptance. While terms for 10, 50, 70, and 90 follow the base-ten system, unique terms for 20-20 counting remain dominant, as seen in nassa chebam (20 + 15 = 35), rather than sumsa (30 + 5 = 35).

This counting system and other similarities, such as specific terms, the practice of rambam, and the liberal use of alcohol, align the Shaukas with the Munda branch. According to Mr. Dinkar, the Himalayan languages differ from Tibeto-Burman languages in ways that closely align with the Munda languages.

Mr. C. Collin Davis, in An Historical Atlas of the Indian Peninsula, classified the dialects of the Shauka region, along with some areas of Nepal, as Himalayan languages distinct from the Tibeto-Burman family. These Himalayan languages potentially include the Shauka region, Marcha of Chamoli, Kinnaur of Himachal, and Newar of Nepal. Kumaoni and Garhwali were classified as Pahadi (Aryan) languages, while Ladakhi, Balti, Burushaski, Naga, Garo, and Kuki were grouped under the Tibeto-Burman family. Similar to how Hindi has incorporated words from Urdu and English, the Shauka dialect has assimilated terms from Tibetan, Nepali, and Hindi over time. Originally a blend of Munda, Dravidian, and Aryan linguistic elements, the dialect evolved further with these additions. Given the proximity of Tibet and Nepal, and the extensive interactions the Shauka people had with these regions, such linguistic influences are unsurprising.

If one were to remove the Tibetan and Nepali words commonly used in the Shauka dialect today, many original terms would still be intact. Elderly members of the Shauka community continue to use some of these native words. Notably, the dialect contains a significant number of Sanskrit-derived terms. For example:

• 'Masi' for ink

• 'Da' for the verb 'to cook'

• 'Ma' for 'no'

• 'Bhandu' for 'vessel'

These words have direct parallels in Sanskrit. Additionally, some terms have evolved from their original Sanskrit forms. For instance:

• 'Kvath' for the verb 'to boil'

• 'Sucha' for 'to give'

• 'Gim' or 'Gi' for the act of swallowing, derived from the Sanskrit root 'Gri'

The word 'Syiri' for 'son' aligns with the English 'son' and the Sanskrit 'Sunu.'

Grammatically, the Shauka dialect shares similarities with Sanskrit. Unlike Chinese, where verbs do not indicate number or tense, the Shauka dialect, much like Sanskrit, distinguishes between three numbers (singular, dual, and plural). This feature is evident in verb conjugations and noun declensions, reflecting a grammatical structure akin to that of Sanskrit. To illustrate the distinctions of number and tense in the Shauka dialect, consider the following examples:

A folk song by Shauka community women in their own dialect

Western Bengal, Bihar, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Nepal, and the Terai region also have the Munda language, which, like ancient languages, has three forms of numbers (singular, dual, plural). For example, Hād means man, Hādkin means two men, and Hādko means many men. In the Munda language, the word for twenty is "Kuri." In the Hanka language, "Kura" refers to 20 "Nali" (a measure of grain). Grain may have been used as a medium of exchange. It is clear that the Shauka language belongs to the Munda family and later underwent full influence from Sanskrit.

In this language, there is no distinction of gender. It can be compared to the Kumaoni dialect, where even though it is a distorted form of Hindi, it does not have gender distinctions. Here, gender distinction is only apparent in caste-based nouns. For example: the men of Bundi village are called Budiyaal and the women are called Budiyaali. This is similar to how, in Hindi, "Kshatriya-Kshatriani," "Nar-Nari," and "Goonga-Goongi" are used. To indicate femininity, the suffix syaa is added, as in Sososyaa, Bamba syaa, Chagroosyaa. In animals and living beings, gender distinction is made by adding Mbu (female) and Phu (male), and there are distinct words for male and female as well. For example, the word Kol is used for a male calf, and Kalouri is used for a female calf. To indicate gender distinction in Hindi, suffixes are added (e.g., "Baagh-Baaghini," "Hiran-Hirani") or entirely separate words are used in English ("She goat" and "He goat"), and in Munda, Aadiyaakul Baagh and Ranghaakul are used for a female tiger.

In Hindi, one word exists for one gender, while a completely different word is used for the opposite gender, like Purush (man). The Shauka dialect also follows the same method for gender distinction. For instance, Mvu Raham means mare, Furahm means horse, Rithi means husband, Rithisyaa means wife, Syiri means boy, and Chmai means girl. It is clear that the form of the Shauka dialect is highly influenced and transformed.

During the Gorkha rule, these people came into contact with the Gorkhas. At that time, Nepali words also became part of everyday speech. Songs and riddles started to be made in the Nepali language as well. Many words, after being used in daily conversations, became permanently integrated. The reason for this was that there were many things in the Shauka region that were new to the Nepali-speaking people. Words like Panas (a copper-made lamp, similar to the Persian Fanoos), Garhwa (pitcher) are contributions from the Nepali language. Between 650 and 850, during the Tibetan kingdom, many Tibetan words may have entered due to trade connections. The original place of the Shaukas is Darma. The people of Darma established fewer contacts than the people of Byans. Therefore, the Darma dialect is less influenced by the Byans dialect. If we exclude the Tibetan words that entered the Shauka dialect, the original words of the Shaukas remain intact. For example, Dangriya for the Tibetan word Lama, Boyam for Dachyon, and Lauani for Mar (death).

To be skilled and successful traders in Tibet, the Shaukas had to live in close contact with the Tibetans. Just as it is natural for an Indian visiting England for a year or two to start using English words, the Shauka traders, who had contact with the Tibetans for centuries, naturally adopted Tibetan words. Similarly, when the British came to India, words like "Good night," "Good morning," "Hello," "Sorry," "Insult," "Yes," and "No" became part of the everyday language. Even today, many Indians use the English word "Thanks" instead of saying "Thank you." After the events of 1962, the influence of contact on the dialect becomes evident. Since then, the Shaukas have been in contact with Hindi speakers in their winter settlements. As a result, over the course of a decade, more than 25% of Hindi words have been integrated into the Shauka dialect. However, their native Shauka words will gradually disappear over the next decade.

The Shauka language has not only been influenced by Tibetan and Nepali languages but has also been shaped by several other languages before them. The Munda language, for example, is a mixture of Dravidian and Aryan languages. After that, the Yavanas, Shakas, and Huns had a significant impact on it. During the early Vedic period, or even before, the Shaukas likely had a limited vocabulary, which is common in the early stages of any developing society. With these few words, they would have expressed their thoughts. These were primarily Munda and Dravidian words. Words from Kinnar and Kirati languages, as described by Pandit Rahul Sankrityayan, align with Shauka vocabulary. Gradually, the vocabulary grew, influenced by external contacts. The impact of external contact continues to affect this dialect even today. This is why Darma dialect has fewer Tibetan words, while Tinker has more. In Darma, the Shauka Maeli (a word for Shauka) remains completely in its original form. Even today, in the Gwun ceremony, songs sung in Darma dialect are preserved in Darma, Byans, and Baudas regions.

Shaukas have a remarkable ability to quickly adopt and use new words. Every Shauka, when visiting Kumaon, can easily speak Kumaoni; when going to Nepal, can speak Nepali; when in Tibet, can speak Tibetan; and in Hindi-speaking regions, can speak Hindi with ease. They have always been traders, and this skill of adapting to different languages is innate in them, a necessity for becoming a successful trader.

Shauka religion, rituals, and deities have their own set of words and names. There is immense reverence for religion and rituals, with minimal external influence. These words are as old as the rituals themselves. For example, the deity worshipped here is Shyidvai, associated with Riddhi-Siddhi gods. Similarly, Madhyo Mahadev and Mati Bhu Devta are also worshipped. The word for temple is Sathan, and words like Kapata (deception) and Vinti (prayer) are specific to Shauka dialect.

There is a noticeable difference in words even over short distances. Thus, words in Byans, Chaudansh, and Darma seem different. This is due to contact with speakers of different languages in various valleys. As Shauka language has no script, and different geographical circumstances exist, these differences are natural. Dr. Bhola Nath Tiwari also said, "Where there are difficult mountains, the spread of language is limited. In hilly and forested areas, due to less interaction, different dialects develop."

For example, the verb Karna (to do) has different forms in Darma (Gamo), Chaudansh (Syumo), and Byans (Syumo). In Kuti village of Byans, it is Lanchye; the word for "place" is Dhw in Darma, Yida in Chaudansh, and Airvyu in Byans. In Kuti, the word Dakhil is used, while the Tibetan word is Diru. These differences have arisen without external influence. However, many words, such as Tibetan and Nepali terms, show the effect of external contact. This demonstrates that language is acquired from neighboring people and should be considered acquired property rather than inherited property. Most of the words in the present Shauka dialect are acquired. The words preserved in ancient folk songs and stories are the only ones considered inherited.

Many writers have mistakenly referred to the Shauka dialect as Tibetan. However, these words are not a gift from the Tibetan language to Shauka; rather, Tibetan language has been influenced by Shauka and other Himalayan dialects. The first reason for this is that the original words of the Shaukas come from Munda, Dravidian, and Sanskrit. Secondly, as Pandit Rahul Sankrityayan noted, languages from the one-letter family in Tibet were most influenced by India. Dr. Bhola Nath Tiwari also wrote, "The Tibetan script is the daughter of Brahmi, and its grammar is influenced by Sanskrit. It includes Himalayan dialects that, although originally part of the same family, have now diverged.

The following examples further demonstrate the connection of the Shauka dialect primarily with Sanskrit and Hindi. Words like "pāp" (sin), "pāpī" (sinner), "ghar-baar" (home), "man" (mind), "sansār" (world), and "desh" (country) show no significant changes. For heaven and hell, the words "shrig" and "nark" are slightly altered. The word "ḍhāl" (shield) remains in the same form, while "talwār" (sword) has evolved into "talwārī". For yak, the Shauka word is "gal", while in Tibetan it is "yak". The English used "YAK" for it, and it became "yak" in Hindi, although "chawar" or "chawri" was used previously. In pure Hindi, "gawal" and "gaur" are used for yak. The corrupted form "gal" is preserved in the Shauka dialect. The word "karma" (action) remains the same, and "janm" (birth) has evolved into "balvakar" or "jerm". The word for alcohol is "sura", derived from the Vedic word "sura", while "madira" (liquor) is similar to the Hindi word "daru". "Andhe" (blind) is "kona", and "goonge" (mute) is "laato". Other words like "gala", "dhok", "rang", "lugra", "bitha", "akaal" (untimely death), "sukal" (prosperity), and "pathana" have similarities with Hindi and other neighboring languages. The word for "dosh" (fault) is "dokha", while "barsa" (rain) is "barkha", and "poor" is "pooro", which is just a corrupted form, not a different word. The word for "punishment" is "daand", and for "auspicious omen" is "shakun", which remain similar to their Hindi and Sanskrit counterparts.

Some words can be considered unique to the Shaukas, which they developed under specific circumstances. For example, the original word for food is "ja", which is close to the Sanskrit word "jamen". For food, the word "dukalam" is used, derived from "du" (main dish) and "kalam" (side dish), as these were the two main items they ate. Over time, this term came to represent food. While names for foods are unique to their dialect, the word "mauni" (a type of dish) was learned from the Tibetans, and the Tibetan term became common. This can be compared to the words "rail", "torch", and "motor" in Hindi, which were borrowed from other languages.

The names of animals traditionally raised by the Shaukas are in their own dialect, but those introduced from Tibetan influence have Tibetan names. For example, "jyu" (zubu) and "jowa" (horse). To call a dog, the word "chacho o" is used, while for animals in general, "lele" is used, and for calling goats, "ainya" is used. The word "chhaya" to scare birds is similar to the Hindi word "alela".

Shri Dabral has written about the dialects of Byans, Chaudansh, and Darma, stating that "these three dialects belong to the Tibetan-Burmese family," but he also mentions that "this dialect also contains words from the Kirati language as a substrate, and there is influence from Aryan languages in its vocabulary and grammar." He notes the names of villages like "Baun Son" and "Dugatu", which are recorded as "Bonal", "Sonal", and "Dug". By using examples of village names with the letter "D", he attempts to prove the Tibetan influence. However, it is likely that the Shaivite Shaukas gave names based on the shape of the lingam, such as "Baling", "Nagaling", and "Ruli Balling". If this is interpreted as Tibetan influence, it could be argued that many mantras like "Glind", "Klind", "Uung", "Nung", and "Pung" are Tibetan in origin.

Some words in the Shauka dialect may indeed seem Tibetan. These include words like "aag" (fire), "ghee" (clarified butter), "namak" (salt), "chai" (tea), and "aadmi" (man), where "myi", "mar cha", "jya", and "mi" are used. However, some of these words have their own forms in the Shauka dialect, such as "launi" for ghee. In Tibetan, "mar" refers to butter, not ghee, while the Shauka word "labu" is used for butter. "Jya" (tea) is a word borrowed from Tibetan. The word "mi" for man is Tibetan, but the Shauka dialect also has its own word, "mansatya", for a human being. Thus, the word "manish" is a corrupted form in Shauka for "man".

The Shauka dialect has undergone significant changes due to the temporary lifestyle of the Shaukas, their trade-related interactions with nearby regions, and the lack of a script. As a result, the older generation of Shaukas uses original words that are now unfamiliar to the younger generation, who have adopted words acquired through contact. It is my belief that without literature and a script, the Shauka dialect will be completely extinct in just a few years. A few years ago, an attempt was made to preserve this dialect by using the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc., as different vowels and consonants, adding marks to them. However, this effort failed due to a lack of higher education and knowledge of grammar. Officials from the Information Department have been helpful in preserving Shauka culture by composing and collecting folk songs related to it. It is unfortunate that the educated youth of today, who could preserve it, are using their native dialect less and less. To protect this culture and language, the youth here must change this trend. The Shauka dialect has become a mixed form, a "khichdi" (a mixture), with its original words and borrowed words from other languages.

It is inappropriate to label this dialect as Tibetan-Burmese just because some words have been borrowed from external contact or because an outsider may not understand them. Outsiders, unfamiliar with it, may perceive all Shauka words as the same. Hence, they assume that the Shauka dialect consists of only around 50 words. The truth is that this dialect is rich and vast. For example, in Hindi, the words "upar" (up) and "neeche" (down) are used to describe locations to the north or south, floors in a two-story house, directions when climbing or descending a mountain, and corners of a field. However, the Shauka dialect is so rich that it has separate words for each of these concepts: "yu-thu", "yerto-yurvbu", "loksa-phunsa", and "yerchyam-panchay". Similarly, in Hindi, there are words to describe various ways of walking, such as running, walking with style, stumbling, and swaying. In the Shauka dialect, there are even more words: "jynkai", "patkali dhakai", "lakyi ballo", "tokchygai", "thangkai", "fankai", and "chanchon poushyigai". Additionally, there are metaphoric expressions like "daukatyi rham" (like a steady horse) or "pannmalyena" (like a slow-moving ox). This clearly shows that the Shauka dialect has a rich vocabulary.

Just as the Hindi language today incorporates a significant number of words from Urdu and English, should we then label Hindi as Urdu or English? Similarly, the Shauka language is independent. Just as Hindi remains complete without the inclusion of Urdu or English words, the Shauka dialect remains complete even if we exclude the Tibetan and Nepali words that have entered daily speech.

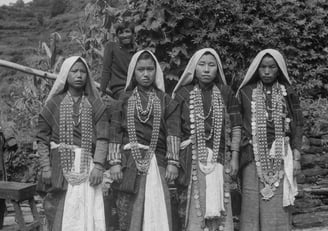

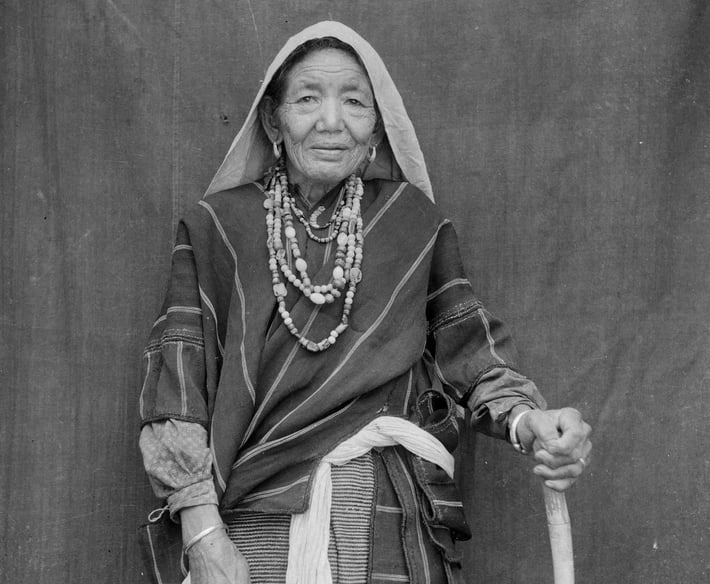

clothing and ornaments

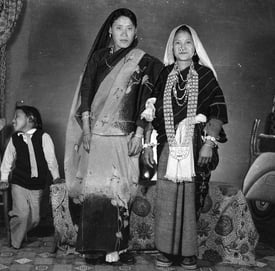

In addition to the economic system, the lifestyle, clothing, ornaments, and means of entertainment of humans allow for the assessment of their standard of living. The following lines describe these aspects. The clothing of the Shokas has changed over time. Today, we see them wearing Western-style clothes. Just a few decades ago, the Shoka attire was different. Now, they can be seen in coats and pants, sarees and blouses, salwar kameez, and lungis. The description of the original attire is as follows:

Men's attire

The basic garment for men was a long robe, which closely resembled the Rajput angarkha. This gown or long coat reached down to the knees. It provided protection against attacks. They wore a turban (byenthlo) or a shylay (a Vedic term for a cap) on their heads. This was made of silk or castor oil fabric (safa byenthlo). It was likely used for protection from the sun, cold, and the blows of sticks and swords. Later, a cotton cloth was also used as a turban. Below the waist, they wore a churidar-style pajama (khag khasi or gaizu). This garment was introduced by the Shakas in the first century BC and AD. A white cloth was used to tie the waist. This cloth was called jyogyam. The men's berko or chedar, and the women's kanchpai, are also Vedic-era draped garments. These garments were all white. Both khasi and ranga were made of wool. Some colors were made from silk and thread.

Women's attire

The basic garment, consisting of chyu and bhala, is called chyumbhala. Bhala is worn below the waist, and chyu is worn above the waist. The chyumbhala is made of wool, with artistic stripes woven into it using cotton threads. It is dyed in only two colors. The blue color is called tinchyu (resembling ink blue), and the red-orange color is called manchyu. Colorful silk threads are used to create floral patterns on the borders. A thick thread, called cholchai, is added along with the stitching, which enhances the beauty of the chyumbhala. The chyu has half sleeves, and the front part of the sleeve is covered with a piece of cloth called ranklachai. This attractive garment is made from getak (a fabric with stripes of various colors). On their heads, women wore a cone-shaped hat called chyuhti, made from white cloth with floral patterns, which hung down their back. A hat, made in the same way as the chyumbhala, called chukla, was once worn along with the chyumbhala. This is a gown-like garment worn on the head. On their feet, women wore woolen bandai, which were tied below the knees with a ribbon called bachijyam. A long white silk or cotton cloth called jyujyam was used to tie the waist, similar to the men's attire.

Children's attire

Until a few years ago, young children wore coats and shirts with hats on their upper body, and on the lower part, they wore saltaraj. Girls used to wear ghaghri (also called jhugla) until they were about 20 years old. This garment is referred to as jhuku in Dharma. It is primarily made from colorful fabrics such as chheent (printed cloth). This frock-like garment is adorned with floral patterns. The ghaghri is also tied at the waist with jyujyam.

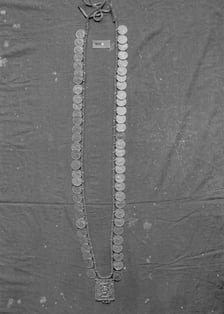

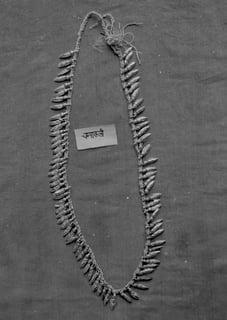

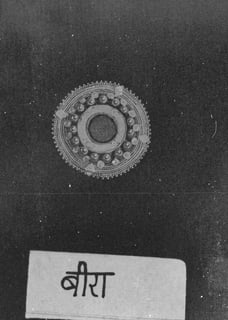

Jewelry

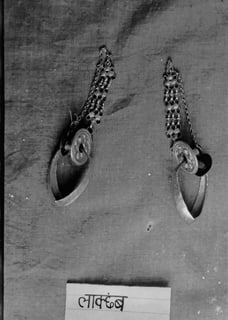

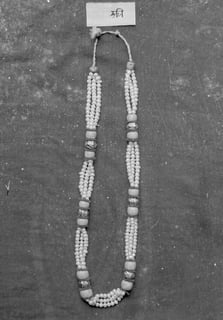

The word "Sali-Puli" in Shouka dialect is synonymous with jewelry (Sa = clay, Li = fruit). In this society, necklaces made from clay or mud were worn initially, indicating that this practice dates back to the Vedic era. Even today, poor women wear necklaces made of clay. Like the Vedic era, men also used to wear some jewelry until a few years ago. Women wore bangles, rings, n (kada), necklaces like Kanthi, Khongli, Baladung, Chandrar (Chandrahara), Champakli, Chyuch, Sisabhi, Arapali, Joko B and Pateli Bali. In Baladung, coins were threaded. They wore nose rings and earrings made of gold and other ornaments. There were no specific jewelry pieces for the feet. Men wore Lachhep in the ear and n (kada), which is also prevalent in Hindu culture. The Karnabhed ritual takes place here, where during Mait-Dev (in-law worship), an uncle gifts his nephew a silver kada (n). A child wore the kada until they reached adolescence, after which it was up to them to decide whether to keep it or discard it. I had the opportunity to see tribal women from Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Assam wearing these same jewelry pieces. I was astonished by the similarities. These ornaments are still prevalent in regions like Tonda, Jonasari, Boksa, Tharu, and Santhals in India. Not only the shapes but also the names of some of these ornaments share similarities. Based on this, I am compelled to say that the Shouka people belong to the group of indigenous tribes in India. Here, gold and silver Mundari (Lachhep) are worn on the hands. Men wear them on just one finger, but women wear them on all five fingers. Sunpatti, the daughter of a Shouka woman named Rajuli Shoukyani, used to wear 20 rings on all ten fingers. Ghibra is a type of jewelry where the spikes on both edges serve as pins. This helps in fastening the edges of a shawl or blanket (Kapchpai). Until a few decades ago, women used to wear Singh and Kasturi teeth set in gold and silver as necklaces. There is also a necklace made of red clay beads, named after the Syepali fruit, which is inexpensive and worn easily by poor women. Because of its red color, it is also called Mansali. This necklace is mentioned in the story of Kyen-Chamai, the daughter who performs the death rites. After contact with Tibet, the use of Munga (zuru) and Pirouja (Iyu) emerged, which were Tibetan influences. These precious ornaments are primarily worn by daughters-in-law. Before that, there is no evidence that the women here used Munga and Pirouja. Young girls in Chhoti Ganga are also fond of these ornaments. Little boys would wear shells or beads found in the sea as jewelry around their necks. These are no longer in common use, but the evidence of this suggests that the Shoukas’ ancestors came from places near the sea, likely from the plains of India.

Language and Dialect Issue

Language is a medium through which cultural exchange becomes possible. Therefore, the dialect or language holds significant importance for every society. The Shauka dialect is scriptless, which is why the Shaukas were unable to give their history a literary form. Their history remains limited to folk tales. Due to the lack of a script, they were influenced by Tibetans and Nepalis in trade contacts, and today, Hindi has also found a place in the Shauka dialect. The Shaukas now speak not only Hindi but have also incorporated many English words into their speech. The native Shauka synonyms are fading away. The Shaukas of Johar have completely adopted the Kumaoni dialect.

It is essential for the Shaukas to develop a script for their dialect in order to keep it alive; otherwise, they should choose Hindi as their language. Adopting Hindi would strengthen India's unity and integrity, but for the Shaukas themselves, this would not be ideal. There are many who wish to preserve their culture and native language, but in doing so, they will inevitably lose their unique identity. The conclusion, therefore, is that their dialect needs protection and encouragement. To do this, the original Shauka words and those that have fallen out of use must be rediscovered, which are preserved in folk songs and stories. Just like the Roman script, a script for Shauka could be developed. If this dialect had its own script, it could rival any literary tradition. The Shaukas' history lives on in their folk tales, but in the absence of literature, it remains ineffective, mute, and constantly changing its form. This is why both indigenous and foreign writers have written distorted accounts of their history. To counter this, literary works need to be created, but the Shaukas had no script nor a voice to do so.

Currently, the Shauka dialect consists of approximately 10% Tibetan, 40% Hindi, Sanskrit, Dravidian, and Nepali words, and 50% words that no longer exist in any language. These words are from the language of the Kinnar and Kirat people described in the Ramayana and Mahabharata. The union of Lord Shiva and Parvati is mentioned in connection with the inclusion of these Kinnars and Kirats. It is also mentioned that Parvati's mother, Meena (or Mina), was the Goddess of the Himalayas. Today, the word for mother in the Shauka dialect is Meena or Mina. Many words in this dialect are from the Kol, Bhil, and Munda tribes, as well as Latin, Roman, and French, which should be considered as the proto-Aryan language. However, now the use of Hindi words is increasing. Without a script, in a few years, the Shaukas will find it difficult to preserve their dialect, and historians and researchers will not succeed. To preserve it, the Shaukas must replace the Hindi, Nepali, and Tibetan words with the original Shauka words in daily conversation. The Shaukas need to abandon the inferiority complex towards their language that the current generation holds. For all this to happen, two things must be kept in mind: First, India's integrity must not be compromised, and second, the Shaukas' culture must remain alive at its core. Such tasks can only be undertaken by the Shaukas themselves. If the All India Radio centers also provide some space for the Shauka dialect, it would be in their best interest.